In Buddhism, a self is created every time we engage in any of the four kinds of clinging (upadana). This is something we do repeatedly as we go about our day, and it is because of this that we are unable to enjoy any kind of lasting well-being (or as the Buddha put it, we suffer). Before we look at these four kinds of clinging and how they operate, it is important to define what we mean by a “self”.

What is a Self?

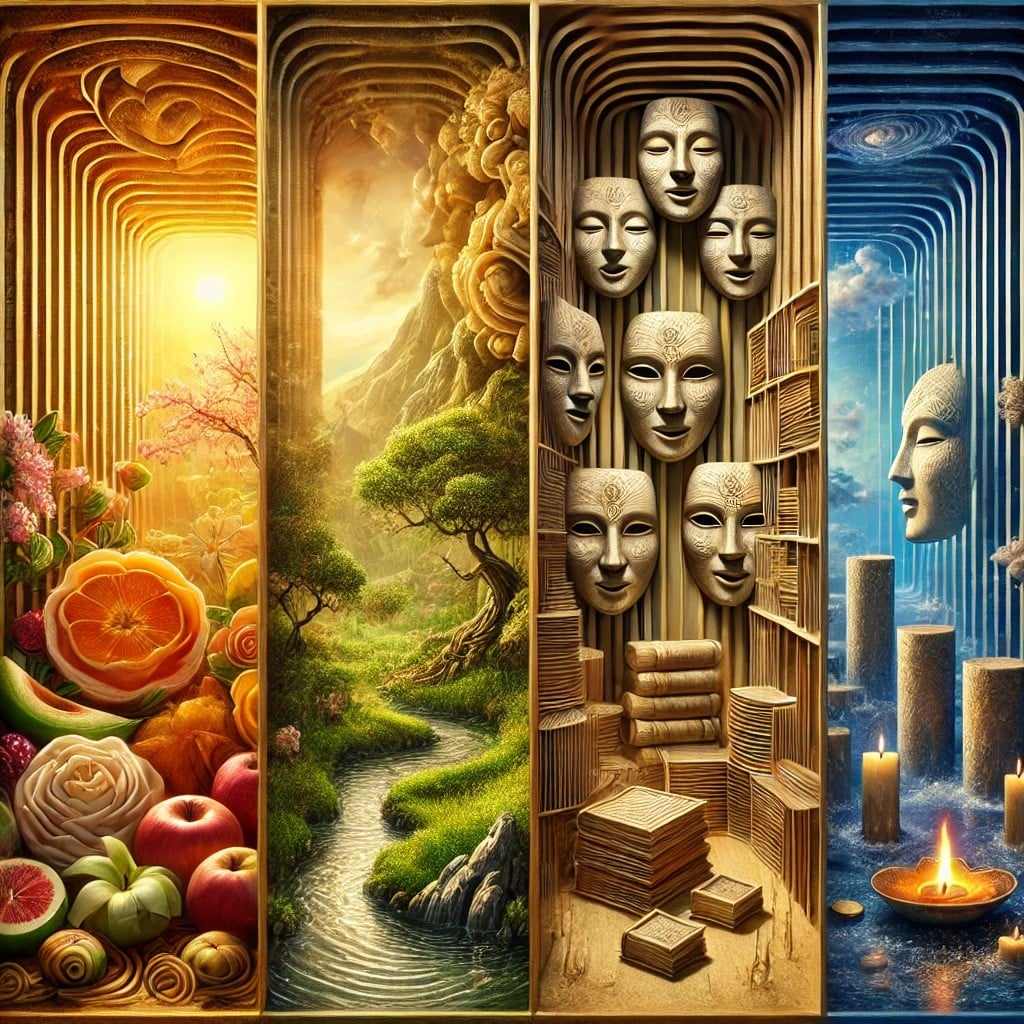

A self is something we create when we become hypnotized by certain patterns of thinking. We identify with these thoughts (cling to them) in a way that radically alters our experience. We can divide these patterns of thinking into four kinds:

Clinging to Sensual Pleasure

The mind orientates to experience by labelling objects as either pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. Most of this is purely subjective (e.g. people can label football as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral). Life is a procession of changing conditions, and problems arise when we cling to what is being labelled in these terms.

Let’s make this easier to understand. I’m going to be using an example to illustrate how the four kind of clinging work in the real world. Imagine you go to the shops to buy a new hat. You are proud of your new purchase, and you can’t wait to show your friends. When you meet up with them later for dinner, nobody mentions your new headwear, and the mind labels this as unpleasant. You attach to this label in such a way that you start to feel bad, and you yearn to feel good. You may say things to yourself like “I shouldn’t be feeling so bad”. If we get too caught up in this, it could ruin the entire evening.

The way experience works is kind of like a conveyer belt that carries along sights, sounds, smells, tastes, thoughts, and physical sensation. Each of these gets labelled as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. If something gets labelled as unpleasant, it doesn’t really matter because the next thing can be labelled pleasant (your friends don’t notice your hat, but they praise your new top). When we cling to something that is momentarily being labelled as pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral, we get stuck. We suffer even though the incident has long passed.

Clinging to Views

Our mind is full to bursting with beliefs and opinions about how the world is, how we should be, how other people should be, and what should be happening. These aren’t even really our views but stuff we’ve picked up along the way. When we notice something coming into conflict with these views, we can start to suffer.

Going back to our new hat. We may believe that if friends care about us, they should notice when we buy new clothing. If they don’t, they are being rude or inconsiderate. We then find ourselves consumed by thoughts such as “how dare they”, or “that’s the last time I show them any consideration”.

Clinging to Rites and Rituals

There is an old saying that if you want to make the gods laugh, tell them your plans. Having plans and habits can be useful for navigating life, but if we become overly attached to these, it leads to suffering. What is happening can be perfectly wonderful, but we may be unable to see that because it wasn’t what we expected.

So, we turn up to dinner with our new hat with expectations of how that was going to go. Our plans are thwarted, and because we have attached to them, the whole evening now feels wrong.

Clinging to Personality

We all have an idea of who we are. The problem is that this will always be inaccurate and incapable of capturing our complexity. When things appear to contradict our view of who we are, we can feel threatened and attacked.

Going back to our example, if we view ourselves as a snazzy dresser. The failure of our friends to notice our hat could feel like a personal attack. We may feel like a failure or a fraud because of the lack of recognition of our fashionableness.

Self or No Self

The problem with self (or more correctly selves) isn’t that it arises but that we mistake it for being real. In fact, part of the practice can be to deliberately create a self (e.g. in loving kindness practice).